The Art of Mastery, Innovation, and Rediscovery

Reflections on the Sunflower Series and Experimental Innovation

At the moment, I'm immersed in two distinct artistic projects, each demanding a more deliberate and thoughtful approach than I typically apply. This newfound focus arises from my engagement with psychological theories, particularly those concerning Innovation Style. One of my projects explores the theme of Spanish beach vacations and the expectations placed on families, revealing how our personal fixations often thwart our own dreams. The other involves reviving a series of paintings based on macro photographs of gardens I took years ago in Chicago. The latter project, I’ve realized, was never truly finished, and I'm now revisiting it with fresh insight.

The garden series is an exploration of experimental innovation, a process I’ve come to understand deeply over time. This style of creation, which champions intuitive discovery, can be seen in the works of scholars like David Galenson. In his book Old Masters and Young Geniuses: The Two Life Cycles of Artistic Creativity, Galenson explores how artists’ careers often follow different patterns: some pursue their work with deliberate, methodical development, while others, like experimental innovators, push forward intuitively, discovering their artistic direction as they go. The sunflower series I'm working on is a perfect example of this experimental process.

Sunflowers, in their earliest stages, are truly alien creatures—bizarre and otherworldly before the bud opens. They captured my attention one summer when I stumbled upon a pack of sunflower seeds that produced unusually tall flowers with multiple heads. At the same time, I was photographing secret spaces in Chicago, places where wilderness overtook the urban environment. The Sears Tower loomed above me, and I’d have full cell phone bars, which was a rarity in the early 2000s. The sunflowers and these hidden wild spaces spoke to me in an uncanny way, each bearing an unusual beauty that compelled me to create paintings and drawings. However, I failed to fully connect the pattern of the sunflowers with their surrounding plants—a pattern I’ve only now rediscovered.

For my beach house series, I’m still working through prototypes, closely following Picasso’s process, which demands that I continue experimenting until I can truly confirm my direction. Picasso’s approach involved revisiting works until he recognized something undeniable, and I’m hoping this project will yield similar insights. But it hasn’t quite coalesced yet, and as with Picasso, I hesitate to write about it prematurely. Our expectations often blind us to the divide between our intentions and the work itself, much like how writers can become "word blind." This is an important point to reflect on, and I’m resisting the urge to rush into conclusions prematurely—although it might take me a couple of years to see clearly what I have and have not actually accomplished. They say that the artwork no longer belongs to the artist when it is complete which is why sometimes it's important to leave a little extra reflection time to remove unintended shifts in visual ideas and message. So, more on that later.

The Experimental Innovation Process and Mastery

The heart of the current work in the sunflowers series revolves around experimental innovation—a term I feel aptly describes my ongoing process of rediscovery. I recently realized that this concept ties directly to a long-forgotten lesson I learned years ago during my brief exposure to Chinese brush painting. The experience—combined with my background in design and Makerspace teaching—has given me a framework for understanding the role of Chi (氣) in mastery.

The concept of Chi, central to traditional Chinese philosophy, involves the flow of energy that permeates the body and the world. While I am not claiming to fully understand Chinese brush painting, my encounter with it profoundly affected my approach to art. In 1997, I was in the midst of dropping out of my MFA poetry program due to financial troubles (my first brush with healthcare financial armageddon). In the chaotic aftermath, I found myself working at the Smithsonian, which led to serendipitous encounters with brilliant curators and master artists. There, I learned the significance of objects—how they were imbued with philosophies and belief systems that transcended mere craftsmanship. This experience helped me overcome the insecurity I had long held about the value of objects as cultural markers.

During this time, I also took a Japanese brush painting class, which led me to meet Master Bojin Chen when the campus offered Chinese brush painting. She was a small, energetic teacher who immediately noticed my intense focus on mastering every detail of the craft. One of her first critiques was that my Chi was "terrible," and she insisted on guiding me through physical exercises—shaking my arms, making me jump—until she was satisfied that my energy was better aligned. The results were nothing short of magical. I began creating some of the best works of my life, filled with an intensity and flow that had eluded me before. What struck me most profoundly was how this process connected deeply with the energy of the brush and the marks I made.

Mastery in this context is not about perfect technique alone but about embodying the energy of the act itself. Chinese brush painting, which dates back thousands of years, is a tradition rooted in memorization and repetition. An artist's journey – in this ancient context – is about pushing their ability to replicate their master’s work until it is indistinguishable from the original. This was essential in preserving traditions long before the advent of written language and visual pictograms. Its my guess that the tradition is what leads inevitably to pictographic writing in the first place; generations of wisdom finding visual form.

The Sunflower Series: The Rediscovery of Chi in Art

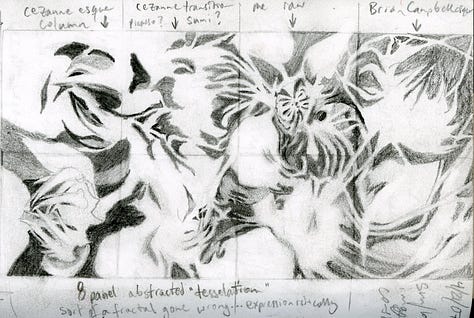

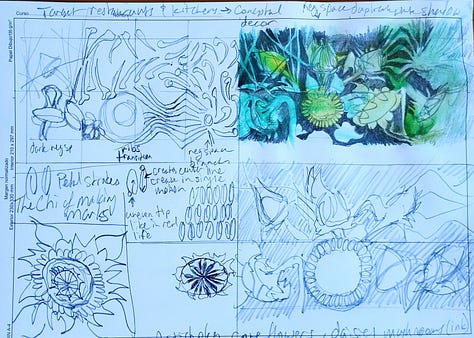

Which brings me back to the sunflower series. The act of repeatedly drawing the petals of the sunflower—each line an exploration of balance between flow and accuracy—reactivated something in my own artistic process that I had forgotten. I’ve included images from my sketchbook where you can see the direction of my pencil strokes. As I worked, I sought to balance the spontaneity of the gesture with the precision needed to create a composition that was both dynamic and controlled.

The key to what I’m describing lies in the moment when every stroke of the brush or pencil becomes fused with awareness. (I’m pretty sure this happens as the cerebellum becomes fully myelinated or interconnected supporting a fluent movement that can be slowly and deliberately refined). Time slows down, and the artist’s hand moves with a sense of singularity—a moment where the distinction between the mark being made and the body making it begins to dissolve. After several repetitions of the same composition, variations emerge naturally, each offering a non-disruptive surprise. The joy of this process is profound; it becomes an act of mastery that draws on both intuition and precision, something I’ve experienced as a musician when playing a difficult chord progression or bending a note on a harmonica. There is an energy to mastery that goes beyond the technique, one that I can only describe as transcendent.

In this process of discovery, I see the parallels between experimental innovation and conceptual innovation. The latter involves planning and feedback, ensuring that the work offers something deliberate and valuable to the viewer. But the joy of discovery—of creating without knowing exactly where the process will take you—has a unique power. It is an act of faith, where failure and success blend seamlessly into moments of profound satisfaction. And while this can be grueling, it is ultimately a deeply human act of connection to the traditions that came before us. These are, after all, the traditions that formed the world that we know.

Conclusion: The Art of Discovery and Transcendence

I am not claiming to fully understand the intricacies of Chinese brush painting or to have unlocked all the mysteries of Chi. I promise you, I have not. But I do feel a deep connection to something ancient and vital when I draw or paint in this mindset. For lack of a decent term, I think of it as a “mastery mindset,” but its really more like what Elizabeth Gilbert describes so well in her TedTalk about creativity and daemons; the mindset allows the channeling of something we can perceive but that is beyond language. So, I guess for now I will call it “Chi Mindset,” because that is the context in which I found it. (apologies if that is in any way objectionable, its just I don’t know a better term, yet…)

The act of making a mark on the page is, in some way, a time machine—a connection to our shared human experience that transcends culture and history. It’s not just about the mark; it’s about the fleeting instant that unifies us all through the power of creative expression. Beyond Asian brush traditions from Ancient Greek potters to Medieval stone masons, all cultures have had countless unsung creative heroes who knew this as a way of life, not as a personal creative insight. By comparison, I’m probably a dabbler by comparison but the insight feels invaluable.

In the future, I’d like to explore how this process of mastery connects with flow theory and other psychological frameworks. For now, however, I leave you with this thought: the hours spent wrestling with creative challenges offer unexpected moments of connection with the human experience, lead to a form of transcendence that resonates in the body, making you feel as if you’ve been struck and you resonate like a bell. And that feeling? That’s the joy of creation, the joy of mastery—pure and unshakable. Whether you just doodle in meetings or in the back of the classroom or have serious art habits, give it another go. The payoff is entirely worth the trouble.

Bibliography

Galenson, David W. Old Masters and Young Geniuses: The Two Life Cycles of Artistic Creativity. Princeton University Press, 2006.

Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. HarperCollins, 1990.

Harris, Marc. Chi: The Power of Energy in Chinese Art and Medicine. Oxford University Press, 2003.